Here I put the spotlight on Cuba’s political state and the impact it has on their footballing landscape, with defection popular in a country governed under a strong communist system…

The writing “Viva Fidel” translates as “Long Live [Castro] Fidel”, supporting the former President of Cuba who spearheaded the Cuban Revolution. (pic credit: cuba-junky.com)

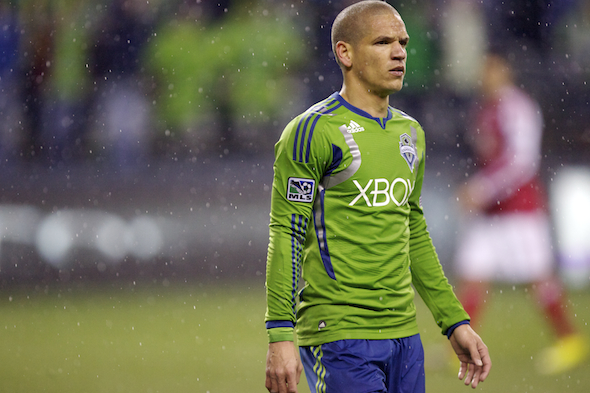

The Osvaldo Alonso Model

Osvaldo Alonso’s story is something incredible. Now a first-team regular at Major League Soccer (MLS) club Seattle Sounders, his journey to the United States required bravery, quick-thinking and hard work. It is a journey that many Cubans try and make year on year: to leave their homeland of Cuba and start a fresh life in the US. For some the decision turns out to be life-changing, for others things don’t go quite so to plan and they have to deal with the consequences.

Born in San Cristóbal, a city in the Artemisa Province of Cuba, Alonso grew up playing with the ball at his feet. He sums up his childhood as “Go to school, play soccer, be with my family, my friends.” His father played the sport and Alonso was influenced, saying “he’d always take me to a field to play with him…”. From humble beginnings kicking the ball about on the streets, “with a ball and two rocks” as goalposts, Alonso shared the same dream as many children around the world. To play professional football. He worked his way up through the Pinar del Río team and his performances alerted the attention of the national football programme. By age 21, Alonso had represented the seniors 17 times and was captain of the national U-21 team. He had hit a wall in the sense that “I didn’t have further goals to reach” as Alonso looked to his future development. In Cuba, there is no professional football. The Campeonato Nacional (16 clubs split into four groups of four teams each) is the highest level in the Cuban football pyramid and none of the league’s players are paid, with facilities and pitches of low quality. The idea of playing abroad in the US, in a professional, competitive environment, is a very enticing one for many aspiring Cuban players. But actually doing it is an extremely difficult process.

Just 90 miles separates the southernmost point of the US, Key West, and Cuba. (pic credit: CDC Gov)

The ‘Wet feet, dry feet policy’, which originated under former President Bill Clinton’s administration, was put in place to help Cuban citizens defect to the US. A Cuban caught on the waters between the two countries with “wet feet” is sent home, while those who make it to shore with “dry feet” are given a chance to remain in the US and later qualify for “legal permanent resident” status and US citizenship. This scheme does have its drawbacks, though, because if a Cuban person doesn’t make it to shore then they could face serious repercussions from the Cuban government, such as a jail sentence. It’s very risky business. After all, it is illegal. However, this didn’t deter Alonso from having a go back in 2007, inspired by ex-international forward Maykel Galindo who had successfully gained access to the US two years previously. On international duty with Cuba at the 2007 CONCACAF Gold Cup, held in the US, Alonso identified this trip as the perfect opportunity to escape. It was in Walmart (American version of cheap groceries store) that Alonso and his teammates were walking around, browsing clothes. Carrying a backpack with $700 inside it, Alonso’s mission was simple: to exit the building as quickly and efficiently as possible. He was under no illusions concerning the risk involved, explaining “Always when you’re afraid, you have to be aware of what’s going on around you.” Fearless, Alonso walked out of the front door of the Walmart, found somebody who spoke Spanish and called a friend. Hours later and he was on a bus heading for his friend’s house in Florida.

Nine months later – with Alonso’s immigration paperwork completed – and Alonso had secured a place with Charleston Battery, a club playing in the third tier of the American football pyramid (USL Pro), following a successful trial. At this point he hadn’t got US citizenship, eventually gaining it in the summer of 2012, four years after his initial escape. At the Battery, Alonso was given a fair crack of the whip and made a major impact on the team, repaying the faith shown in him by the management staff. In his debut season, he started 31 games and contributed seven goals. Alonso was presented with numerous awards, including the Battery’s Player of the Year as voted by his teammates and USL Pro Rookie of the Year. It was just the way Alonso had planned it, with his performances in his debut campaign earning him recognition from the MLS. In 2008, he signed for Seattle Sounders, and since has gone onto make 142 appearances, some of which whilst wearing the armband, predominantly as a defensive midfielder.

The 28-year-old was and still is a trailblazer for Cuban players to defect and try and gain a professional contract in the US. A few others did so before him but their success was more limited, such as goalkeeper Rodney Valdes who defected to the US during the 1999 Pan-American Games in Winnipeg, Canada. Cousins Rey Ángel Martínez and Alberto Delgado followed suit in 2002, escaping at the 2002 Gold Cup, telling the team they were going to make a phone call in the hotel lobby. Instead, they ran out of the hotel and traveled in a taxi to Martinez’s uncle’s house. Both went onto appear for the Colorado Rapids in 2004. And then the aforementioned Galindo stayed in the US after he arrived in the country while on international duty at the 2005 Gold Cup. In the same year as Alonso defected, Lester Moré did too and he also ran out for the Battery in 2008. Now at the age of 37, Moré is still going strong, donning the shirt of Los Angeles Misioneros in the USL Premier Development League. There have been examples of defection in the national women’s programme, too, with Yisel Rodriguez and Yezenia Gallardo disappearing during an Olympic qualifier in Vancouver in 2012. Even with Cuban ballet dancers who appeared in Miami earlier this year.

Although seen as a traitor by the Cuban government, Alonso still has his own fans. He’s represented as a role model by some young, up-and-coming players in his homeland, who aspire to follow his career path and make a living out of the sport in the US. And at club level with Seattle, the supporters love his tenacity, desire and commitment in the tackle, nicknaming him “Honey Badger”. One thing that Alonso notes as particularly hard about leaving Cuba is the fact he had to wave goodbye to his family, not knowing if he’d see them again anytime soon. This can prove a massive emotional barrier and homesickness is something that Alonso had to cope with, as he slowly but surely found his feet in the US, beginning at the Battery. His wife and children are now with him in Seattle. There has previously been some talk of the midfielder potentially playing for the US at international level, despite wearing the jersey of Cuba in the past. The only thing preventing him from making the switch is the Cuban Football Federation, who must formally provide permission. Alonso can never play for his country of birth again, however, it is virtually impossible that the Federation give him the green light to switch allegiance. Not now, not after defecting. Alonso remains a proud Cuban, though, claiming “I’m from Cuba, I love Cuba. But, you know, my decision changed everything. For me, I have everything to be happy.”

The Battery’s Cuban Link

Indeed, if it wasn’t for the welcoming nature of Charleston Battery, then maybe things would have been very different for Alonso. But ever since taking him on in 2008, the club has continued to keep its door open for fellow Cubans looking to make their way into America. Two years ago, prior to a World Cup qualifying match in which Leones del Caribe were not able to name any substitutes against Canada in Toronto, four of Cuba’s players and the team psychologist, Ignacio Abreu Sánchez, made the brave decision to defect to the US. Three of those four players were youngsters Heviel Cordovés, Maikel Chang and Odisnel Cooper. Their story is similarly remarkable to that of Alonso’s, as the trio escaped from their hotel in Toronto, ran six blocks and used a stranger’s phone to call Cordovés’s cousin who resides in Canada. The next morning they were on a bus and making their way to Niagara Falls, from where they approached the border and got in through the “wet foot, dry foot” policy. All three were handed try-outs at the Battery and all three went onto play for them, with Chang still there (as of July 2014). The manager, Michael Anhaeuser, is a big advocate of giving Cuban players the chance to play and impress. Because Cubans are eligible to become American citizens, they do not count toward the limits on international players, which is an advantage.

More details can be found on The Post and Courier website.

Significantly, players of the Cuban national team receive a paltry 8-10 dollars a month, which isn’t enough to live on. Under communism, there is a principle of equality whereby just because you are physically talented, doesn’t necessarily mean you deserve higher living standards. Yordany Álvarez, who defected along with six others in 2008 following an Olympic qualifier hosted in the US, spoke to KSL Sports about the low money income. Álvarez, having hung up his boots prematurely aged 29 in August this year after undergoing a series of tests for a medical condition he suffered during a match in June, was considered one of his country’s most naturally gifted players. He told USA Today: “Cuba has good soccer players but the conditions are bad — no cleats, bad coaches, bad food. All my friends in Cuba have retired. They don’t want to play anymore because there is no money.” It is no wonder that so many Cubans yearn for the chance to move north as the pay is simply so poor. The US are generally happy to assist in the process of taking in Cuban defectors, for they disagree with Cuba’s communist beliefs. It is fair to say the two have got very incompatible political systems.

It is intriguing, then, that Cuba have enjoyed success on the pitch over the last few years. In 2012, the senior men’s team were crowned Caribbean Cup champions after overcoming Trinidad & Tobago 1-0, Marcel Hernández scoring the winner in extra time. This was the nation’s first title at this tournament and as a result they received $120k. In 2013, the U-20 side qualified for the World Cup at that youth level for the first time in their history. Despite finishing bottom of Group B, registering zero points, scoring one and conceding 10, the very fact Cuba had even participated was a worthy achievement. So clearly the talent is there in Cuba, if not the professional conditions to match. Perhaps there is an urge to get to these major competitions and shine in order to attract the attention of overseas clubs who might open doors, and that is the underlying motivation. The New York Times ran an article in May 2012 profiling the rise of football in a baseball-dominated country. One 10-year-old boy, Emanuel Fernández, said “It’s our game, fun and fast.” Baseball is still classed as a very dominant sport, on the same popularity level as hand-rolled cigars, but football is becoming increasingly fashionable. The worry for Cuba, however, is whether the very best players will choose to stay in their homeland or flee for the chance to play professionally abroad. Most would prefer the latter option.

So what does the future hold for Cuban footballers? If the national teams build upon relative recent success then there may be an even greater chance of the country’s players defecting, to the detriment of the domestic game. It seems this is an ongoing pattern and as long as Cuba is communist, it looks like there is no immediate end to this challenging situation.

By Nathan Carr

—————————————-

Thank you for reading! Feel free to leave any constructive feedback in the comments box below.

Reblogged this on Blood, Gold & Glory.

Pingback: Escape From Cuba: Risking All For Football | Year Zero Soccer

Pingback: 2015 CONCACAF Gold Cup: Caribbean-N/C American gap diminishing |

Pingback: October Round-Up: Olympic qualifiers, beach soccer & friendlies |